Palestinians in UN Refugee Camps Live an Illusion Palestinians continue to live as refugees hoping to return to their pre-67 villages now part of Israeli territory.

I recently visited two Palestinian refugee camps run by the United Nations Refugee and Works Agency [UNWRA] near Bethlehem and found the visit to be disturbing. I observed first-hand that Palestinians still plan to return to their 1948-style villages, now part of Israel. They appear to be living in what I can only describe as a “time warp” – an illusion that they will one day return to their former homes in pre-67 Israel.

For example, I was shocked to see at the entrance to the Aida refugee camp a huge “key” that says “Not for sale.” It promotes the notion of a “right of return” that “cannot be bought.” It begs the question, Why does the West allows such a display at a UN refugee camp it funds? It feeds the illusion of a mass “right of return” that ultimately requires the destruction of Israel.

In 1989 I co-founded the Winnipeg chapter of Peace Now because I believed Palestinians would forego a “right of return” to live in a future Palestinian state in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem. I expected these would co-exist alongside Israel, which would be predominantly Jewish. For a two-state solution to be feasible, Palestinians have to forego a “right of return.”

My recent visit negated these hopes.

In UNWRA refugee camps Palestinians live in streets according to the villages of their origin (i.e. refugees and their descendants from Jaffa all live near each other), children’s sports teams are divided according to former villages (i.e. children who are descendants of Jaffa refugees are on one team).

Both UNWRA refugee camps displayed “NAKBA” signs depicting maps of Palestine that included all of pre-67 Israel.

In the Aida refugee camp, long blocks of huge murals showed former Palestinian villages to which refugees hope to return. Be’er Sheva, for example, appeared as a small pastoral village with several houses. Today, of course, Be’er Sheva is a developed city of 200,000.

Memorializing their former lives in this manner feeds their people with unrealistic notions of returning to a pre-67 Israel and perpetuates conflict.

Recently in a Washington, D.C. conference, I met a Jewish peace activist who had volunteered in an art program at the Deheishe refugee camp. She commented that when the children were asked to draw something, they all drew a large key representing the key to the home in the village where their grandparents lived in 1948 – the one to which they hoped one day to return. “It was disturbing to realize that this was the first thing the children drew,” she said.

For a peace agreement between the Palestinians and Israel to prosper, youth in UNWRA’s refugee camps must be taught to move on, upgrade their lives and resettle into nice homes in Bethlehem, Ramallah and the West Bank, not in pre-67 Israel.

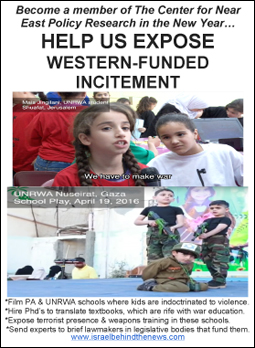

In Deheishe I personally observed on an UNWRA school near the camp’s entrance, a large mural of a female suicide bomber – a graduate of the school. In allowing this mural, the UNWRA school glorifies terror and perpetuates the continuation of conflict because the suicide bomber becomes someone children admire and aspire to emulate. I also saw behind the school a number of other large murals of terrorists who have died to “liberate Palestine.”

It begs another question: Why do Western countries fund a UN school that allows huge murals of terrorists on or near them?

At the Washington conference I also met George A. Laudato of the U.S. Agency for International Development (US AID), their Middle East Bureau. Laudato confirmed that although US AID builds schools in UNWRA refugee camps, it “does not monitor the content” of what is taught in those schools, which he acknowledged, “is a problem.” He described a situation “three to four years ago” at a US AID school in Egypt:

“When I looked at one of the globes in a classroom, I realized the globe didn’t have Israel on it. All the globes in the school were the same [missing Israel]. I knew the American Congress wouldn’t want to be paying for this.”

Laudato insisted that the globes be replaced, but emphasized that normally US AID wouldn’t have intervened. “I intervened because we have had a relationship in Egypt for over 30 years, so I felt I could do something about replacing the maps, but this is not the usual case.”

Andrew Whitley, the outgoing director of UNWRA’s New York office, made headlines in October 2010 at the National Council for US-Arab Relations annual conference saying that it is time to level with the refugees:

“If one doesn’t start a discussion soon with the refugees, for them to consider what their own future might be, for them to start debating their own role in the societies where they are rather than being left in a state of limbo where they are helpless, but rather preserve the cruel illusions that perhaps they will return one day to their homes, then we are storing up trouble for ourselves…. We recognize, as I think most do, although it’s not a position that we publicly articulate, that the ‘right of return’ is unlikely to be exercised to the territory of Israel to any significant or meaningful extent…. It’s not a politically palatable issue, it’s not one that UNRWA publicly advocates, but nevertheless it’s a known contour to the issue.”

When Whitley said this, he was “roasted over the coals” by Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat and others in the Palestinian Authority (PA), and several days later he retracted the statement, apologizing and clarifying that his remarks were “inappropriate and wrong” and “did not represent UNRWA’s views.”

Many refugees claim that Palestinian leadership cannot give up the “right to return” since it is not theirs to give up. They claim that each refugee family can decide what they wish to do—receive a compensation package and live elsewhere, return to the West Bank/Gaza, or go back to their original villages as in 1948 Israel.

Lt. Col. (Res) Jonathan Dahoah Halevy pointed out that Saeb Erekat, as PA chief negotiator, delivered two speeches at Fatah conventions in 2009 in which he said the "right of return" is the individual right of each refugee and cannot be conceded by anyone in negotiations. This is consistent Erekat’s statement in the Guardian, December 2010, and with the comments of Palestinian Huwaida Araf, a key organizer of 2010’s infamous Floatilla to Gaza, at Israel Apartheid Week, Winnipeg.

Questions we might ask would be:

Who in Palestinian society is coming forward to level with Palestinian refugees and their descendants to say that they aren’t going back to their villages in Israel?

Who in the PA leadership is telling refugees in the Bethlehem area camps that they should plan on the Bethlehem area being their permanent residence so they can redirect their energies toward rebuilding their lives and their future?

Laudato insisted that the globes be replaced, but emphasized that normally US AID wouldn’t have intervened. “I intervened because we have had a relationship in Egypt for over 30 years, so I felt I could do something about replacing the maps, but this is not the usual case.”

Andrew Whitley, the outgoing director of UNWRA’s New York office, made headlines in October 2010 at the National Council for US-Arab Relations annual conference saying that it is time to level with the refugees:

“If one doesn’t start a discussion soon with the refugees, for them to consider what their own future might be, for them to start debating their own role in the societies where they are rather than being left in a state of limbo where they are helpless, but rather preserve the cruel illusions that perhaps they will return one day to their homes, then we are storing up trouble for ourselves…. We recognize, as I think most do, although it’s not a position that we publicly articulate, that the ‘right of return’ is unlikely to be exercised to the territory of Israel to any significant or meaningful extent…. It’s not a politically palatable issue, it’s not one that UNRWA publicly advocates, but nevertheless it’s a known contour to the issue.”

When Whitley said this, he was “roasted over the coals” by Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat and others in the Palestinian Authority (PA), and several days later he retracted the statement, apologizing and clarifying that his remarks were “inappropriate and wrong” and “did not represent UNRWA’s views.”

Many refugees claim that Palestinian leadership cannot give up the “right to return” since it is not theirs to give up. They claim that each refugee family can decide what they wish to do—receive a compensation package and live elsewhere, return to the West Bank/Gaza, or go back to their original villages as in 1948 Israel.

Lt. Col. (Res) Jonathan Dahoah Halevy pointed out that Saeb Erekat, as PA chief negotiator, delivered two speeches at Fatah conventions in 2009 in which he said the "right of return" is the individual right of each refugee and cannot be conceded by anyone in negotiations. This is consistent Erekat’s statement in the Guardian, December 2010, and with the comments of Palestinian Huwaida Araf, a key organizer of 2010’s infamous Floatilla to Gaza, at Israel Apartheid Week, Winnipeg.

Questions we might ask would be:

Who in Palestinian society is coming forward to level with Palestinian refugees and their descendents to say that they aren’t going back to their villages in Israel?

Who in the PA leadership is telling refugees in the Bethlehem area camps that they should plan on the Bethlehem area being their permanent residence so they can redirect their energies toward rebuilding their lives and their future?